Record Tropical Atlantic Warmth Continues but for How Long?

A return to seasonal dust outbreaks and more typical trade winds in the coming weeks may pump the breaks but likely won’t reverse the trend

Besides El Niño, the big story this hurricane season has been record warmth across the entire North Atlantic, including the Main Development Region or MDR, the deep tropical belt where most major hurricanes form later in the hurricane season. Waters through the MDR continue to run as warm as they usually are in late August and early September, the historical peak of the hurricane season, and have been a catalyst for unprecedented development of multiple June storms east of the Caribbean. The record Atlantic warmth is the strongest signal to-date of a potentially active Atlantic hurricane season despite a normally storm-squashing El Niño.

Though waters across the deep tropics were running warm all spring, the ocean heat wave took off in earnest by late April. The source of the spike is largely a change in the jet stream pattern that weakened the semi-permanent subtropical high pressure over the Atlantic. Since May, this persistent pattern slowed the brisk east-to-west flowing surface trade winds from Africa to the Caribbean, reducing ocean mixing that typically keeps surface waters from overheating.

To add fuel to the ocean fire, outbreaks of Saharan dust which might veil sunlight as dust cover peaks in June and early July have been largely absent since April. The result is the warmest Atlantic we’ve seen this early in the season going back at least 43 years.

Just this week, we’ve seen an uptick in dust cover across the tropical Atlantic with our first dust outbreak of the hurricane season. Extended range models also suggest a more seasonally-looking subtropical high as we move deeper into July. That said, the dust outbreak isn’t impressive for this time of year and the subtropical high won’t be roaring back, so don’t expect a big cooling of the Atlantic in the near future. Water has a much higher heat capacity or specific heat than air, which is a scientific way of saying it takes more energy to cool it down or heat it up. So even when things change in the atmosphere to cool down the ocean, it takes time to happen. It’s why ocean temperatures peak weeks or longer after air temperatures do.

For now, the Atlantic has ceded its time to the eastern Pacific which saw its first named storm of 2023 form yesterday afternoon, Adrian, which rapidly strengthened overnight and Wednesday morning into the first eastern Pacific hurricane of the year. This is one of the most sluggish starts to the eastern Pacific hurricane season in the reliable record, a surprising development during an ongoing El Niño.

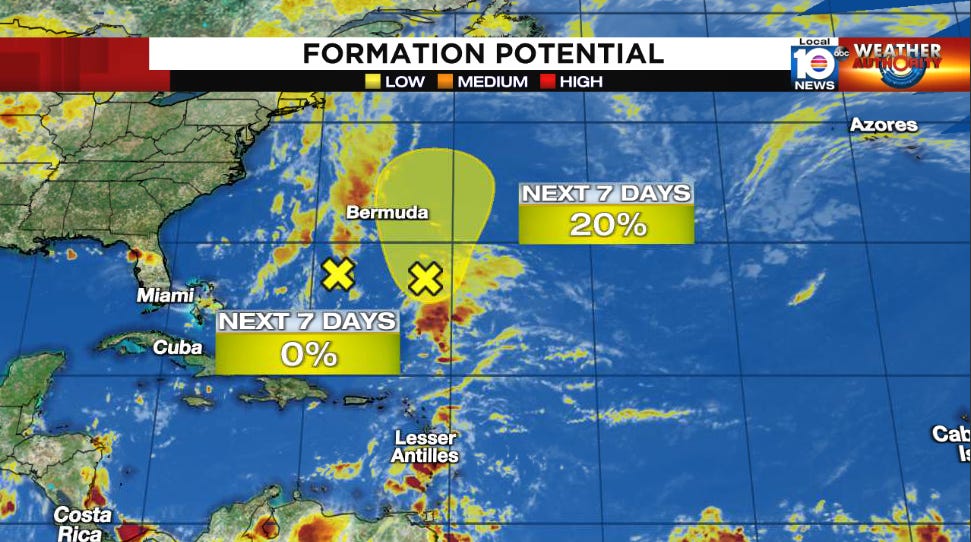

Two areas of low pressure south of Bermuda are being highlighted by the National Hurricane Center, including the remnants of once Tropical Storm Cindy, but neither shows promise of significant development as they remain well east of the U.S.

Depressing but I appreciate hearing what is going on. Thanks Mr. Lowry

I appreciate reading about the triggers that change so significantly in weather.

Thanks for the education.