El Niño's Officially Here. Can It Tame the Atlantic?

El Niño is typically associated with reduced Atlantic hurricane activity, but other factors in 2023 make the forecast less clear

On Thursday, the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center officially announced the return of El Niño, an ocean phenomenon with wide-ranging global weather implications.

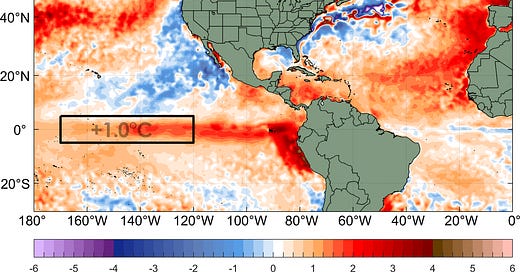

El Niño conditions occur when a strip of waters in the eastern Pacific Ocean around the equator warm to at least 0.5 degrees Celsius above average, with forecasters expecting these conditions to persist for at least several months. El Niño conditions happen every two to seven years on average and are often punctuated by cooler periods known as La Niña. The current El Niño comes on the heels of a nearly continuous La Niña since the summer of 2020 and is the first El Niño since 2019.

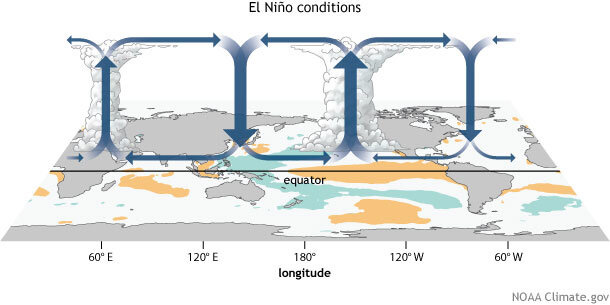

The emergence of El Niño – especially a strong El Niño as many forecasts suggest by later this summer – can significantly alter global weather patterns. In a typical year when waters are warmest across the western Pacific, rising air supported by the ocean warmth gives way to storminess near Southeast Asia, with sinking air and drier conditions across the central and eastern Pacific.

During an El Niño, this circulation pattern – known as the Walker Circulation – shifts eastward, with warmer waters in the eastern and central Pacific giving way to rising air and storminess farther east. The outflow from this rising air and storminess during El Niño events extends into the western Atlantic and Caribbean, where it not only increases storm-busting wind shear – most noticeably across the Caribbean – but dries out the normally moisture-laden tropical skies, as air from the descending branch of the circulation sinks. This usually reduces the number of hurricanes and overall tropical activity in the Atlantic.

Of course, this is the simplified textbook version of El Niño and Atlantic hurricanes. Despite high confidence in a strengthening El Niño in the months ahead, the atmospheric response over the Atlantic is less certain, in part because waters have never been as warm as they are over the tropical North Atlantic. Examining other recent episodes of El Niño coinciding with the peak months of hurricane season, Atlantic waters were generally much cooler than they are today. The tropical Atlantic has been running an astounding full degree Celsius or warmer above its long-term average, blistering warmth that in any other year would signal an active hurricane season ahead.

One thing we’ll be watching for this month is whether we begin to see the typical Atlantic response to El Niño. If the excessive heat in the eastern equatorial Pacific increases rising air over there, we should soon see more sinking air over here in the Atlantic. This would strengthen the subtropical Atlantic high pressure and east-to-west flowing trade winds in the deep tropics, thereby helping to cool off Atlantic waters and ramp up wind shear. The longer we go without seeing trade winds increase in the Atlantic, the more concerning it becomes for later hurricane season activity. It’s something we’ll be following closely in the months ahead.

For now, we expect the Atlantic to remain quiet for near future, with no tropical development expected at least into the middle part of next week.

Without trade winds, the "hot Atlantic would mean El Nino would become ineffective this year, and we would have a storm fest like in 2020, when La Nina was around. It may indeed be El Nino, but if Nature plays her cards right, El Nino can end up acting like La Nina, LOL!!