What a Sizzling Eastern Atlantic may Signal for Hurricane Season

Can a budding El Niño block what's cooking in the Atlantic?

Early in the hurricane season, folks naturally wonder how bad things might get in the months ahead. Of course, no one can say with any measure of skill exactly when or where a hurricane will strike months or weeks in advance (such forecasts, when offered, should be met with a mix of rousing laughter and sharp contempt). The science just isn’t there. It’s why we tell you each and every year to prepare as you would for any other hurricane season.

Forecasters can, however, offer some skillful predictions months out more generally on whether there will be more or fewer hurricanes than average. So while we may not be able to say today how bad it’ll be for South Florida, we can look to reliable predictors to say something about overall Atlantic hurricane activity.

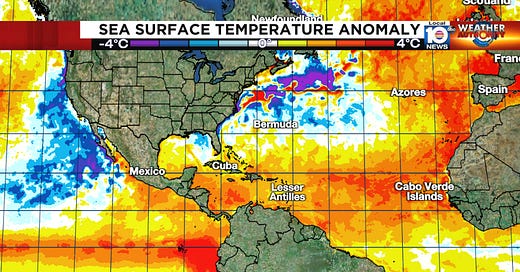

Seasonal hurricane activity is driven primarily by two competing factors: El Niño (or its counterpart La Niña) and north Atlantic water temperatures. It’s the hurricane season see-saw. When waters in the eastern part of the Pacific near the equator are much warmer than average – during El Niño conditions – storm activity in the Atlantic tends to get reduced. The opposite is true for Atlantic waters. When waters in the tropical Atlantic are warmer than average, we tend to see heightened storm activity.

For the Atlantic in late May and early June, we specifically look to the eastern north Atlantic close to Africa where a north-to-south moving current known as the Canary Current can impact important atmosphere circulations that regulate water temperatures across the Main Development Region (MDR) of the tropical Atlantic.

Seasonal forecasters find that when the Canary Current is much warmer than average this time of year, it weakens the subtropical ridge of high pressure that controls the strength of the east-to-west flowing trade winds in the deep tropics. When the subtropical high weakens, so do the trades, which lessens ocean mixing that would otherwise cool down the deep tropical Atlantic. Weaker trade winds and a warm MDR are dry kindle for hurricane season activity.

This year, the part of the Atlantic in early June with the strongest relationship to overall hurricane season activity is the warmest it’s been over the 42-year period of record.

Looking at other years trailing 2023 with a warm late May eastern Atlantic – years like 2017, 2008, 2020, 2010, and 1995 – we find very active hurricane seasons. The one key difference between those years and what we’re expecting in 2023 is they didn’t also see a strong El Niño.

The eastern equatorial Pacific is the warmest it’s been relative to average since 2019 and models forecast that warming trend to continue into the fall. If these forecasts hold, the change in circulation patterns should help to dampen what has historically been a setup for big hurricane seasons in the Atlantic. It’s why groups like Colorado State University and NOAA – those showing the highest forecast skill over the years – are calling for an average year despite the record Atlantic warmth. But even our best seasonal forecasters acknowledge the higher than typical uncertainty in this year’s forecast, which run the gamut from well below average to well above average across the two dozen or so seasonal forecast groups.

Thankfully this week the tropical Atlantic remains quiet. The window for development of the unusual non-tropical area of low pressure about 600 miles southwest of Portugal has closed. Otherwise, a blanket of dry air draped over the western Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico will keep any disturbances at bay through the weekend.

I didn't think that little storm had anything more than a fighting chance. Hurricanes and tropical storms have never developed in that part of the world. Why would this little storm do so now? Well, it's not gonna develop; and even if it had, and got the B name, the weather in Spain and Portugal would not have been any different than what it is now. You would never know you were having a tropical entity. In those weak "shorties" as this one would have been, there's no way to really tell the difference according to the symptoms of the oncoming storm.