No Eastern Pacific Named Storms Yet Despite El Niño

Historically the tropical basin comes alive during the month of July

With the remainder of the week quiet in the Atlantic, we’ll check in on the eastern North Pacific, which started its hurricane season back on May 15th.

The hurricane season out there starts 15 days ahead of the June 1st Atlantic hurricane season due to a more conducive environment supporting earlier development, especially for hurricanes. On average, the first hurricane typically forms by late June in the eastern Pacific compared to mid-August in the Atlantic. By the end of June, the east Pacific has typically seen about 10% of its annual tropical activity while the Atlantic is usually through only a paltry 2% of seasonal tropical activity.

But so far in 2023, we’ve yet to see a tropical system of any type – tropical depression, tropical storm, or hurricane – in the eastern Pacific. To date, it’s the latest start to the eastern Pacific hurricane season (as measured by the first tropical cyclone) since 2019 and the fourth latest start since the turn of the 21st century. This may come as a surprise given the abnormally warm eastern Pacific waters, especially closer to the equator from the blooming El Niño. Yet at this point the lack of activity isn’t too out of the ordinary.

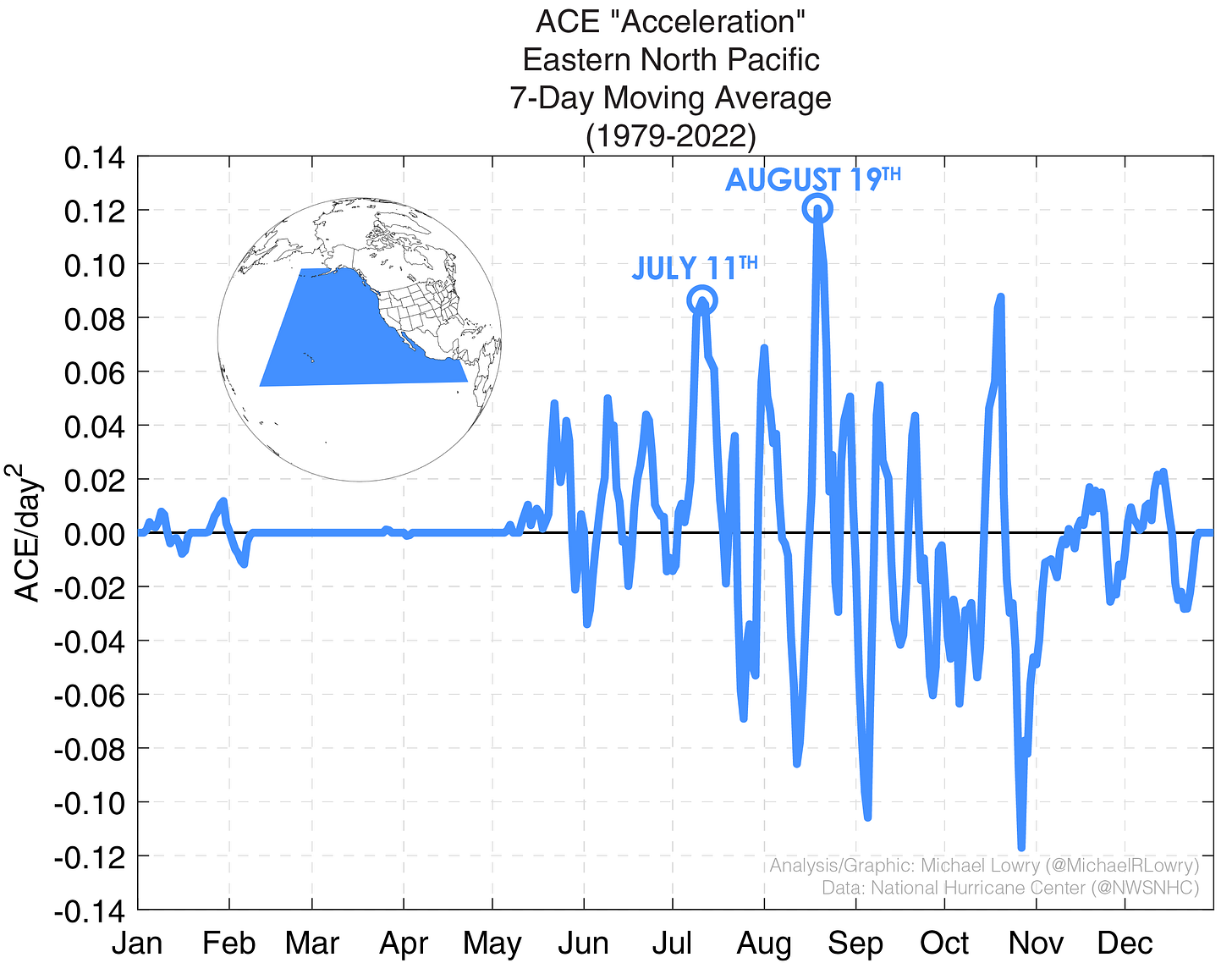

The eastern Pacific really starts cranking in July. Though we often begin to see a sputter of activity by late May into the first few weeks of June, it’s typically around the second week of July that activity really ratchets up. We can visualize this acceleration of activity using a gauge I call ACE (for Accumulated Cyclone Energy – the proverbial hurricane season yardstick) acceleration. Like a heartbeat monitor of typical tropical activity, ACE acceleration shows us the livelier periods of the hurricane season.

The eastern Pacific season so far has been tepid largely due to what’s happening over in the western Pacific. Several strong typhoons – including Category 5 Super Typhoon Mawar at the end of May, the strongest storm so far in 2023 – doubled what is the usual tropical activity in this part of the world. All of this storminess and rising air in the western Pacific has resulted in sinking air in parts of the eastern Pacific normally prone to storm formation. The resulting subsidence has put a lid on disturbances trying to spin up in recent weeks.

That may change in the next week or two as the western Pacific settles down. The National Hurricane Center is currently monitoring two areas for development in the eastern Pacific, the first disturbances of note in 2023. While both areas have only a low chance of development, they are the first signs of life a full month into the eastern Pacific season.

While we’ll keep an eye on a few early season tropical waves into next week in the tropical Atlantic, none of our models suggest significant development potential for now.

The rising air/sinking air phenomenon is known as the Madden-Julian Oscillation(MJO)Mike. Factors other than just El Nino can determine when these tropical entities finally get together. That includes the MJO, and how it behaves.