Tracking Several Early Season Tropical Waves

While it’s too early in the season to expect development, they are a sign of what’s ahead

In Monday’s newsletter, we highlighted favored areas of tropical development in June, including the western Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and western Atlantic. Today we turn our attention to the disturbances that originate over Africa – known as tropical waves – that often serve as seedlings for many of our strongest hurricanes later in the hurricane season.

Not all tropical waves develop into tropical storms or hurricanes. In fact, most don’t. Of the roughly 50 or 60 that roll through the Atlantic each year, only a handful or so grow into full-fledged tropical storms or hurricanes. As we mentioned yesterday, the vast majority of these happen in August and September. This means most tropical waves move through the Atlantic with little fanfare, bringing the occasional rain squall – but not much more – to tropical locales.

The first tropical waves of the year usually start rolling into the Atlantic by mid-May. In 2023, the Tropical Analysis and Forecast Branch (TAFB) at the National Hurricane Center began tracking the first Atlantic wave on May 15th. It's in June, however, that we see a noticeable tick up in the number of tropical waves leaving the African continent and surviving the trek into the Atlantic. These disturbances continue to roll off Africa every 3 to 5 days throughout the hurricane season.

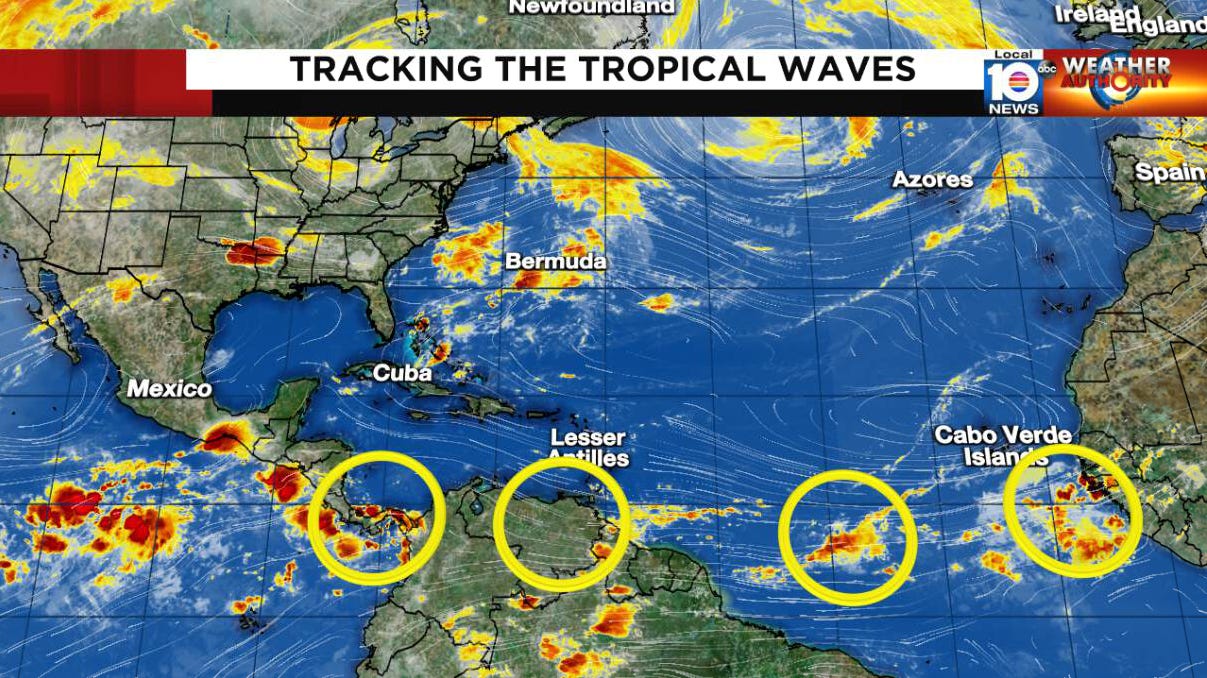

Today, we spot four of these tropical waves dotting the Atlantic from Africa to Panama. None of these disturbances is expected to develop, as strong wind shear remains an insurmountable early season hurdle.

By late weekend and early next week, a wave emerging in the deep tropical Atlantic shows a little more spunk in our computer models, with shear lessening some east of the Caribbean islands.

That said, in contrast with late June 2022 when shear was significantly below average in the deep tropics and NHC began advisories on a potential tropical cyclone (later Bonnie) east of the islands, our models today don’t suggest a serious development window for this one.

As we enter July, we’ll be keeping a wary eye to the main development region and these fledgling tropical waves as they interact with some of the warmest June waters we’ve seen on record in the tropical Atlantic. If El Niño works its usual magic, upper-level winds in the western Atlantic and Caribbean should help to combat the favorable thermodynamic profile (ocean heat) this season. As we’ve discussed ad nauseum, however, the tug-of-war between a strong El Niño and record Atlantic warmth is an interplay we haven’t seen in modern memory, which makes the 2023 hurricane season more of a cliffhanger than usual.

thanks again!