Where to Look for Formation the Second Half of June

Another quiet week expected across the Atlantic, but we’ll be watching these areas to round out June

June is typically a quiet month for tropical development across the Atlantic. Historically, only about 6% of all named storms form in June, compared to August, September, and October, which each see about 25%, 35%, and 20% of all named storm formations respectively (80% of named storms and 94% of Category 3, 4, and 5 hurricanes form from August through October). That means we’d expect a named storm about every one to two years in June – on par with November, the other bookend of the hurricane season.

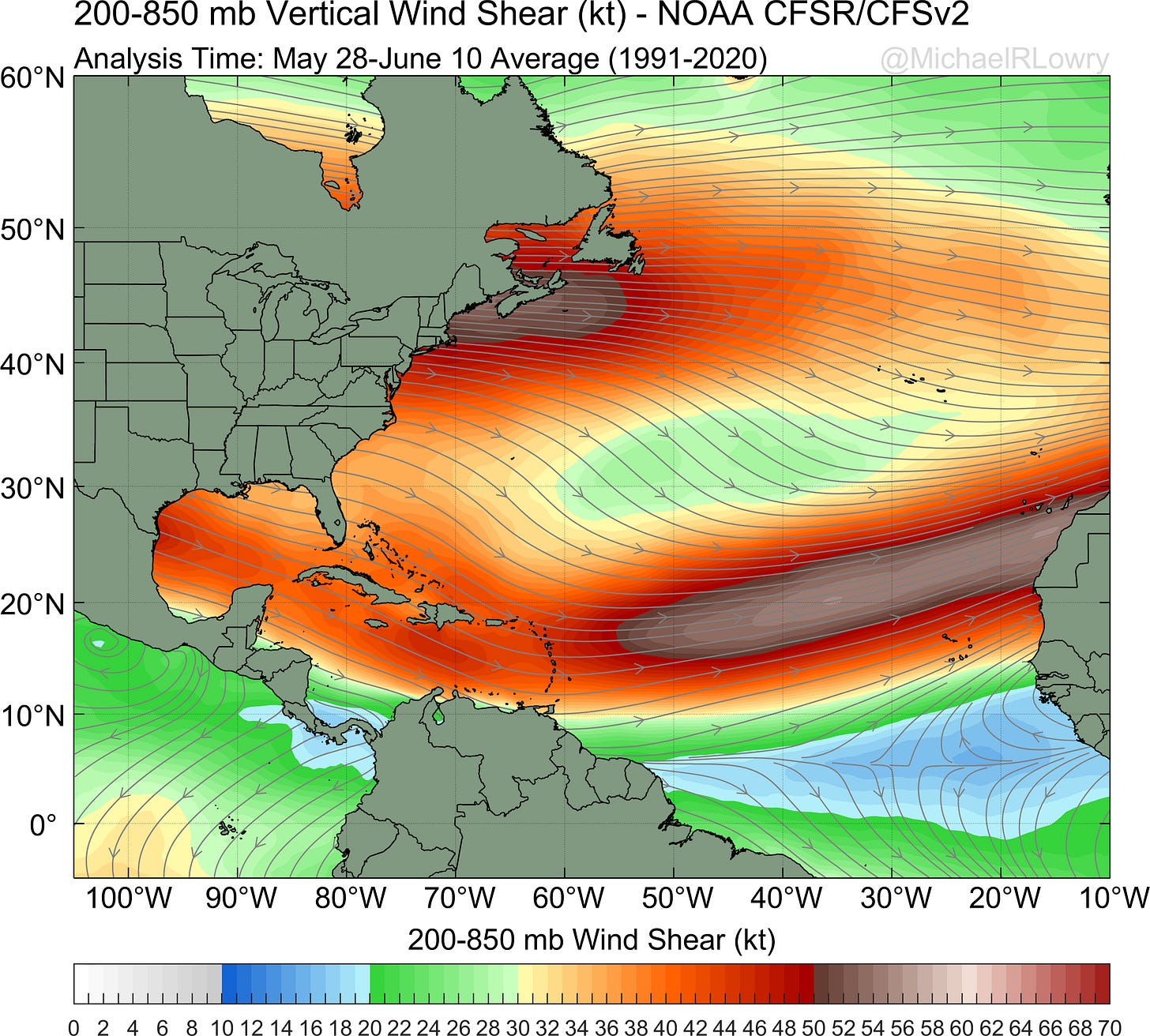

We know a few things about tropical climatology to help us narrow our focus in June. In general, wind shear is the biggest prohibitive factor to tropical formation this time of year. The subtropical jet stream is usually still too powerful for storm formation over the warmer tropical waters.

So while the deep tropical Atlantic systems (primarily spawned from African Easterly Waves or AEWs) comprise 50% to 60% of Atlantic named storms and some 85% of our strongest (Category 3 or stronger) hurricanes, they’re usually not a major player until late July and August.

It explains why you see only a smattering of formation points east of the Caribbean islands in the map at the top of this article.

So what are the triggers for tropical formation this time of year? We often look closer to home for non-tropical low-pressure systems that see a boost from those still strong upper-level winds. This is how Tropical Storm Arlene formed back at the start of the hurricane season. These early season systems often don’t turn into our most formidable hurricanes, but they can still bring significant impacts, especially from heavy rainfall.

We also look down in the southern Gulf of Mexico and extreme southwestern Caribbean Sea for storms spun off from a broad area of spin extending from the Caribbean into the Pacific, known as the Central American Gyre (or colloquially the CAG). Tropical systems spawned within the CAG tend to peak in May and June and again in the fall. The CAG systems that involve some interaction with the jet stream (blue bars in the plot below) are less frequent, but often pull more rainfall north and east out of the Caribbean which can impact us in Florida.

Over the past two weeks, the subtropical jet has been noticeably farther north than its typical position for this time of year.

This might suggest an opportunity for formation in the western Caribbean, but models indicate that window is quickly closing, with a more typical positioning of the subtropical jet through the Caribbean and into the western Atlantic over the next few weeks. This may be a sign of the atmospheric response to the building eastern Pacific El Niño is beginning to take shape.

Those strong upper-level winds for now should keep things in check in the Atlantic. Forecast models don’t show any strong signals for development over the next week.

By next week, models do show some enhanced rainfall tucked away in the southwestern Caribbean. The American GFS model is prone to hyperbole in this area, so beware of its overcooked forecasts beyond 7 or 10 days. If we see any organized activity down here, it’ll likely have to battle the nearby strong wind shear or hop over into the eastern Pacific where conditions are more favorable.

I really appreciate these updates very much. All of this is so interesting!