What a No-Show Eastern Pacific Hurricane Season Could Signal for the Atlantic

The eastern Pacific hurricane season is off to its slowest start on record, which could be a telling sign for what’s ahead in the Atlantic

There’s a sort of feng shui about the tropics: everything has its place. And like the ancient Chinese practice, one of the guiding principles of the tropics is a yin/yang balance to global hurricane activity. It’s why globally the number of named storms averages around 80 to 90 each year without much variation. It’s also why when the Atlantic is chock full of hurricane activity, the eastern Pacific is usually out to lunch (or vice versa).

So perhaps it’s no surprise that this year, while the Atlantic has notched its 3rd most active start in modern recordkeeping (since the since the mid 1960s), the eastern Pacific is off to its slowest start in the reliable records (since 1971) – and by a remarkably wide margin.

The eastern North Pacific is typically a fast-starter compared to the Atlantic, with activity ticking up in earnest by the second week of July. By the end of July, the eastern Pacific is usually through 5 named storms, 3 hurricanes, and at least one Category 3 or stronger hurricane. So far, the basin’s managed to eke out only 1 named storm – Aletta at the beginning of the month – that peaked with 40 mph winds and lasted as a named storm for less than 12 hours. That’s it. Eastern Pacific tropical activity is less than 1% of normal through July 22nd.

In a balanced tropical world, something’s seriously off kilter. Or is it?

Even when the going’s good, the harvest is scarce

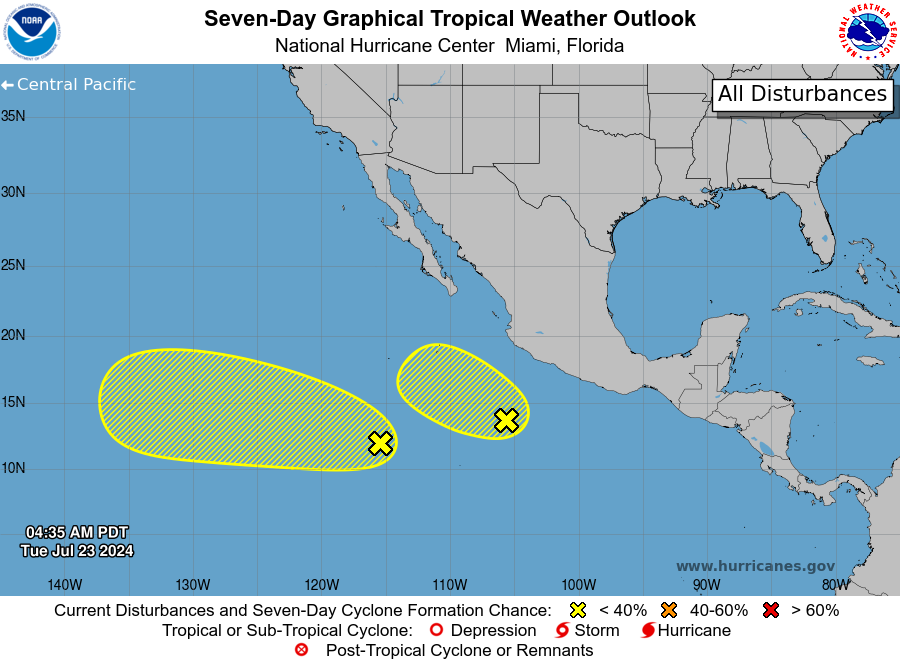

If ever there was a point in the eastern Pacific hurricane season for storm activity, it should be now. To be fair, it’s been trying with several suspect areas identified by the National Hurricane Center this morning.

But the 7-day odds for development remain paltry and if recent history is any indication, these areas to watch may vanish just as quickly as they appeared.

The reality for this hurricane season out west (of Mexico) is that the atmosphere isn’t getting any more conducive for development. As we discussed in yesterday’s newsletter, La Niña is quickly setting in and that means an environment unfriendly to the formation of eastern Pacific hurricanes.

The eastern Pacific has never gone an entire hurricane season without a hurricane, and even in the most muted seasons, we’ve seen a handful of hurricanes. So we’ll see hurricanes there this year, but they’ll be much harder to come by.

Why a dead Pacific is a bad omen for the Atlantic

The feng shui of the tropics spells trouble when there’s an imbalance in hurricane activity. Studies show that while globally the number of named storms hasn’t changed significantly over the past 30 years, some individual basins do show a change, but the change is offset by other basins.

For example, the western North Pacific, on average the most active tropical basin in the world, has observed a significant decline in named storms since the early 1990s, but the north Atlantic has seen a significant increasing trend (unrelated to technological improvements).

Like the long-term trends, when one basin goes down, another must goes up. Every other global tropical ocean basin besides the North Atlantic is running a big deficit so far this season, including the normally busy western Pacific. With such a shortfall, something has to give and the tropics will undoubtedly make up for lost time to get us to the 80 to 90 named storms we should expect by December.

The question is which basin lights up when. Unfortunately for us, it looks like the Atlantic will be the one to pick up the slack left behind by the Pacific this year.

Thank you! Watching the Atlantic closely as we head into August in Tampa Bay

Thanks for informative & interesting posts.