What can be written about the hurricane forever etched into the lives of a generation of South Floridians 30 years ago today?

Hurricane Andrew – which roared ashore near Fender Point along the southern reaches of Biscayne Bay shortly after 5 AM on Monday, August 24, 1992 – sliced a path of destruction through South Florida, annihilating chunks of South Dade County from North Kendall Drive southward through Cutler Ridge, Homestead, and Florida City. Andrew was merciless, shattering windows across downtown Miami, uprooting trees, and felling fences from Broward to Palm Beach Counties. Even the National Hurricane Center – sitting six floors up the 12-story Gables One Tower on Dixie Highway across from the University of Miami – lost its roof-mounted radar in the crucial minutes before landfall, as winds gusting over 160 mph toppled the radar dish, casting forecasters into meteorological darkness just as the worst of the Category 5 hurricane struck.

Survivors describe the hours of agonizing onslaught, homes “breathing” with each intense gust, and the terror of being exposed to the most powerful storm on the planet. The hellish landscape in Andrew’s wake turned once-familiar streets and neighborhoods into unrecognizable heaps of rubble. Everything seems smaller in the aftermath of a hurricane, but especially after a storm like Andrew. The usual landmarks and guideposts – from street signs to gas stations – vanished and the trees that withstood were coated in copper hues, stripped clean of their once-lush tropical foliage.

The images from Andrew are unmistakable: Metro Zoo flamingos huddled in a public restroom, two-by-fours and plywood launched through the thick trunks of royal palms, Burger King’s wrecked corporate headquarters on Biscayne Bay, and the Florida City water tower left standing over the ruins beneath. It’s impossible to capture the scope of Andrew’s carnage across South Dade, but these singular images evoke powerful memories for those who lived through the storm and the nightmare that ensued in the days after.

Andrew was a gamechanger. It not only disrupted the lives of hundreds of thousands of South Floridians, but took an outsized economic toll, at the time the costliest natural disaster in U.S. history. But from the misery sprung action.

Building codes were hardened, making the post-Andrew-standard the gold standard for the country. Although FEMA had been in existence since 1979, the agency came into modern being during the James Lee Witt era in the aftermath of the Andrew response debacle (and former Dade County Emergency Management Director Kate Hale’s desperate “Where in the hell is the cavalry” plea). Major federal reforms post-Andrew sought to accelerate the disaster declaration process, prioritized pre-storm staging of goods and services, and directed FEMA to focus on mitigation and preparedness measures.

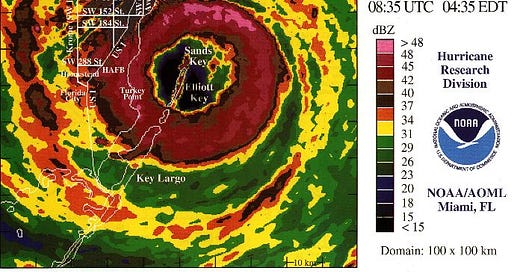

Scientific advancements in hurricane forecasting and communication saw a boost in the years after Andrew. The accuracy of hurricane track and intensity forecasts improved by 75 percent and 50 percent, respectively, since. A cornucopia of new hurricane investigative equipment – from instruments aboard hurricanes hunter aircraft that estimate surface winds from ocean seafoam to precisely tracked instrument packages launched regularly into the eye of hurricanes to high-resolution, three-dimensional hurricane scans from satellites – has revolutionized the way we see and understand storms. What used to be only theory – like the dangerous swirling filaments curling inward and rotating around a hurricane’s inner eyewall – is frequently seen in vivid detail with the technology of today.

Nevertheless, hurricane forecasting is still a young science, response and preparedness is an imperfect science, and communicating hurricane threats is an increasingly complex social science. We’ve come a long ways, but we still have a ways to go.

No one better captures the legacy of Hurricane Andrew than my colleague Bryan Norcross, who guided South Floridians through one of the most devastating and challenging periods in its history.

“The experience, the lessons, and the legacy of Andrew were far more than a time that came and went decades ago,” he writes in his My Hurricane Andrew Story memoir. “For many, the emotions are still raw. The fear, the despair, the perseverance, the eventual collective triumph, despite seemingly insurmountable odds, can never be forgotten.”

And that is what we remember today, 30 years later.

This same storm also caused Cat 3 destructive winds west of New Orleans. It later brought a night of heavy rain in the Northeast, at LEAST an inch and change. I think it was a Friday night in Central New York we had periods of steady, heavy rain that came from Ohio as Andrew was at that point, just an extratropical low, or ordinary low.