From Late June to Early July: Where We Look for Tropical Development

Tropical Atlantic expected to stay quiet this week

Tropical cyclones – tropical depressions, tropical storms, and hurricanes – don’t form spontaneously. They need a spark to trigger convection which begins the process of tropical cyclogenesis – or the organization of thunderstorms into a distinct tropical system. This spark originates from some larger disturbance in the atmosphere. There are a variety of sources of these disturbances, and they often change depending on the time of year.

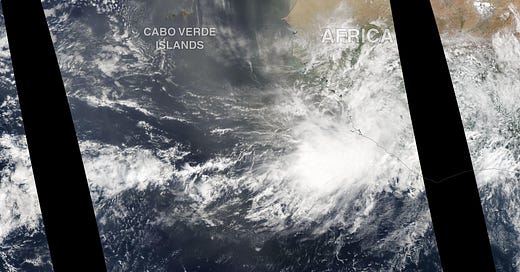

The most famous spark are the disturbances that roll off Africa every three to five days – disturbances called African Easterly Waves (or AEWs), since the ripple in the wind field 5,000 to 10,000 feet up resembles a wave, but in the atmosphere. African Easterly Waves are most notorious because studies suggest they account for roughly 50 to 60 percent of Atlantic named storms and are estimated to be responsible for 85 percent of our Category 3, 4, and 5 hurricanes. Overall, though, African Easterly Waves don’t become the dominant source of our tropical systems until later in July and especially August and September.

Early in the season, like during the first half of June, we often see tropical systems develop closer to the United States in the Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean, or even off the southeastern coast. The most common sources of formation are low pressure areas on the tail end of cold fronts still dipping southward, or, as we’ve seen in recent weeks and with Tropical Storm Alex in early June, the broader area of spin between the Atlantic and Pacific known as the Central American Gyre. As NHC Hurricane Specialist Dr. Philippe Papin found in his research, this broader Central American Gyre is a bigger spark for May and June systems, but tends to be less of a player by July and August.

Over the next few weeks, we’ll begin a transition period, as we branch out across the Atlantic and the atmosphere provides us other sources for tropical sparks. By analyzing where tropical systems have formed historically the last week of June and first week of July, we can get a sense for where these disturbances originate.

Off the east coast and into the Gulf of Mexico, we continue to see the occasional storm form from stalled fronts or from preexisting spin within the Central American Gyre. We also begin to observe, however, the occasional African Easterly Wave take shape in the eastern Atlantic. Off the southeast United States, we will sometimes find large non-tropical thunderstorm complexes (called mesoscale convective systems) form over land and emerge over water to become tropical systems. This scenario happened in 2014, when Category 2 Hurricane Arthur formed from a large thunderstorm complex moving through Georgia and South Carolina.

In general, the biggest threat to the continental U.S. still arises from systems that form closer to home. Although about one in five storms form in the eastern Atlantic once we get to late June and early July (typically from African Easterly Waves), only one in recent memory – Elsa in 2021 – actually made landfall in the continental U.S. So we start to look out to the eastern Atlantic, but the quick forming home brews are still the ones most threatening this time of year.

For now, thankfully, we don’t see anything brewing on the horizon close-in. Some of our longer-range models suggest more defined disturbances rolling into the eastern Atlantic from Africa in the coming weeks, but nothing to get excited about just yet.