Early Season Storms Leave Less Time for Preparation

Quickly strengthening storms and home brews are a recipe for disaster

There’s an old adage in emergency management that our most precious and perishable commodity in any disaster is time. A large part of what makes an emergency an emergency is the limited time available to address the danger at hand. When you’re faced with a medical emergency, it’s both the severity and suddenness of the threat that distinguishes an emergency from a scheduled surgery or procedure. Severe and sudden is a bad mix in the medical field. The same goes for disasters.

Hurricanes are, by definition, severe events. The extreme 74 mph or higher winds of a hurricane, usually occurring over hours, not minutes, can inflict serious to catastrophic damage. Their associated hazards – especially coastal storm surge and torrential rainfall – present a considerable threat to life. Because hurricanes are so large, unlike tornadoes, they take some time to cook, and because of their size, our weather prediction models are better at spotting them and forecasting their movement. Hurricane track forecasts, in particular, have seen tremendous improvements over the past 50 years.

But, despite tropical meteorology being one of the biggest success stories of predictive science, the unexpected plot twists of hurricanes continue to pose a very real concern to forecasters and disaster planners alike. It’s the time component – the quick forming or quickly intensifying storms – that can worsen an inherently severe hurricane threat.

Former National Hurricane Center Director and longtime WPLG Hurricane Specialist Max Mayfield often says his worst nightmare is people going to bed expecting a Category 1 hurricane and waking up to a Katrina or Andrew at their doorstep. Make no mistake, we’ve made noticeable progress in forecasting the intensity of hurricanes, especially over the past decade, but the storms that ramp up quickly through rapid intensification remain elusive, and their occurrence has been increasingly common.

In recent years, we’ve seen hurricanes like Matthew in 2016 or Maria in 2017 strengthen 80-85 mph in a matter of 24 hours. Extremes like Wilma in 2005 or Patricia in the eastern Pacific in 2015 ramped up by 110-120 mph – or from a Category 1 to a Category 5 – in a single 24 hour period. In general, when storms strengthen, if they do so far away from land, it gives us time to adjust our preparations, similar to an airliner that encounters extreme turbulence at cruising altitude. But when storms quickly and unexpectedly strengthen close to land, it’s like an airliner hitting extreme turbulence while on approach for landing – we have less time to adjust, making the threat much more serious.

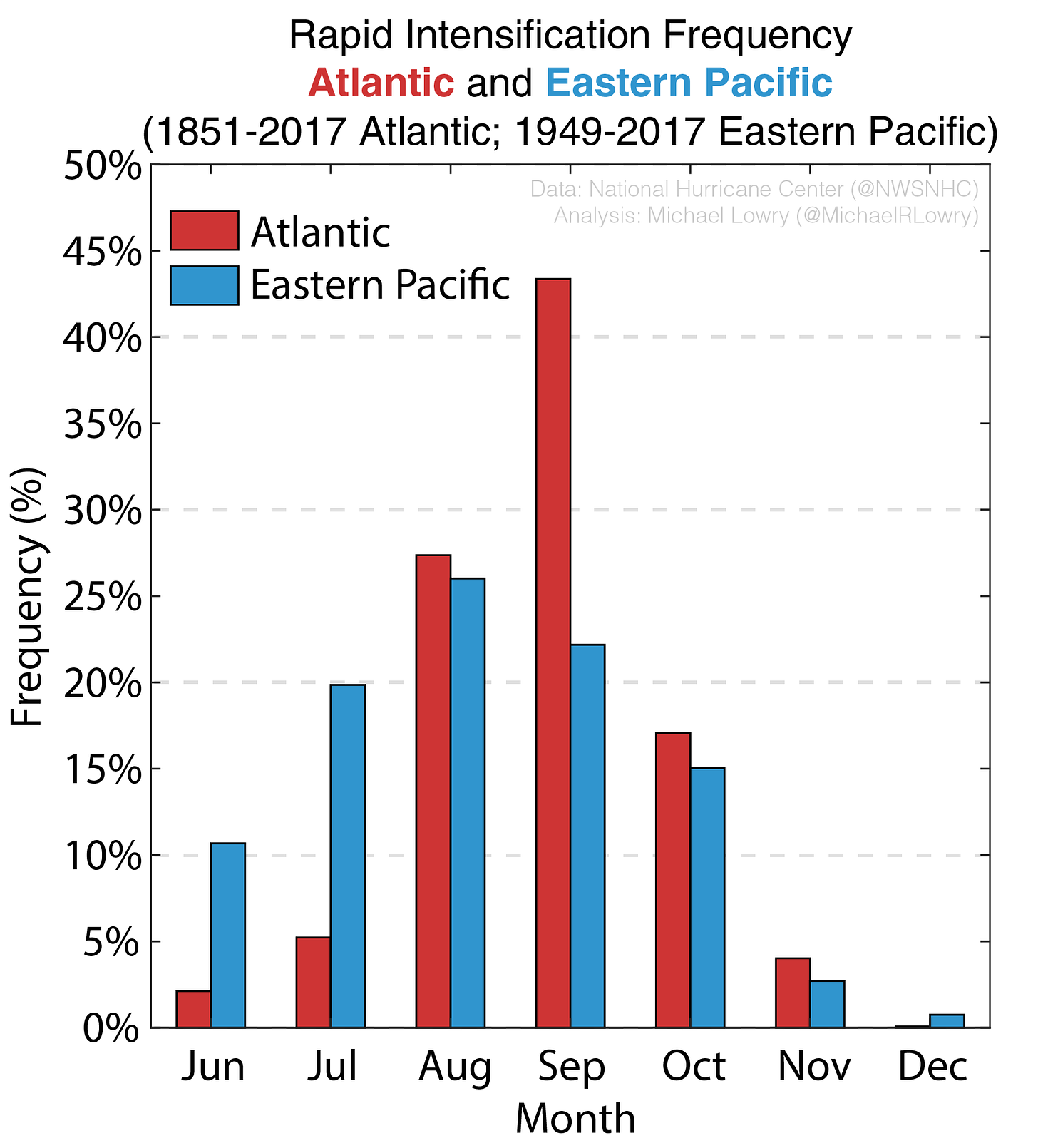

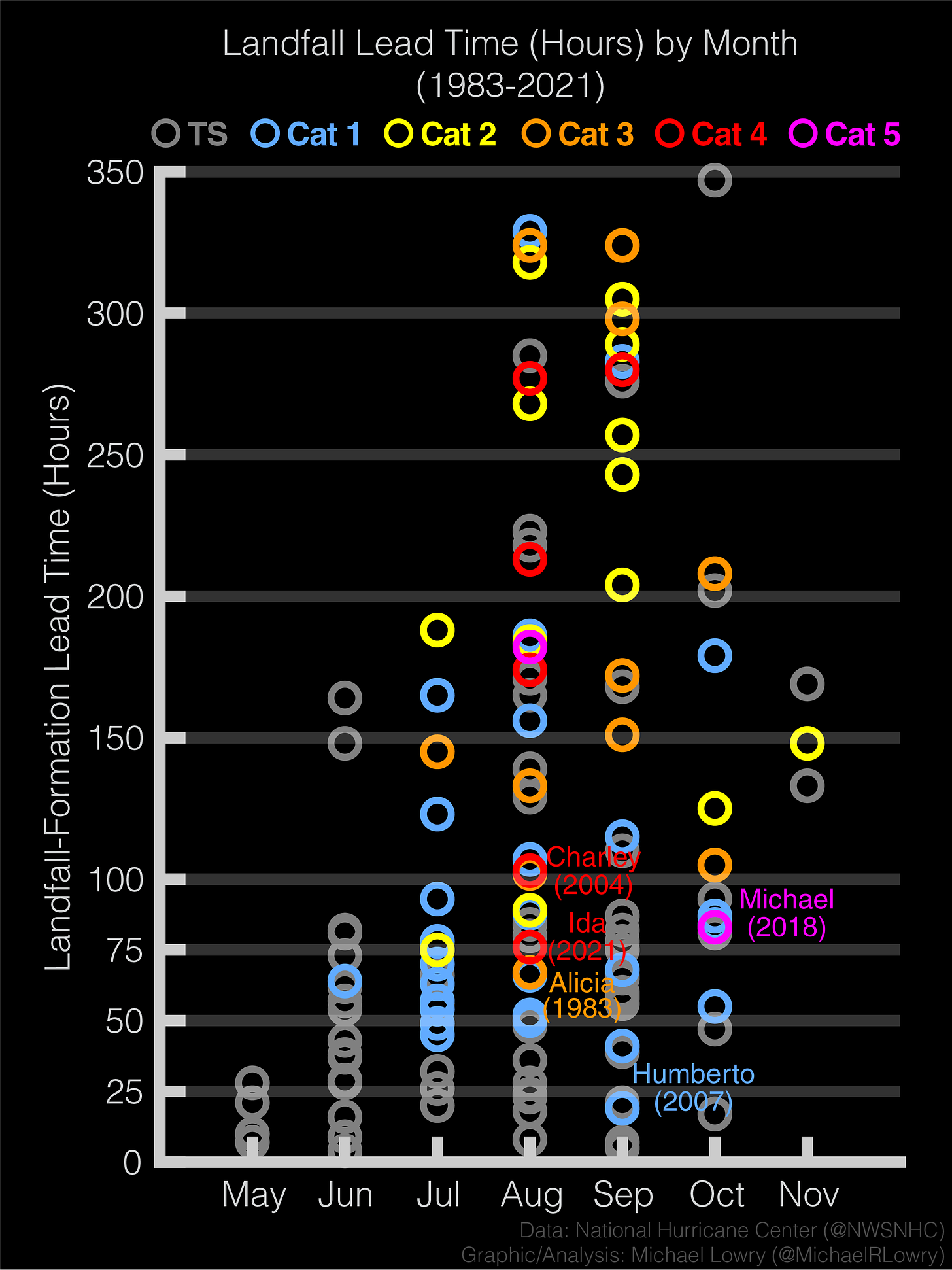

These extreme episodes of strengthening are more common as we get into August, September, and October – the peak months of the Atlantic hurricane season. The season bookends, however, like June, July, and October, are known for storms forming close to home, often along stalled fronts draped over warm tropical waters. These home brews, like their rapidly intensifying siblings, give us less time to prepare and warn the public.

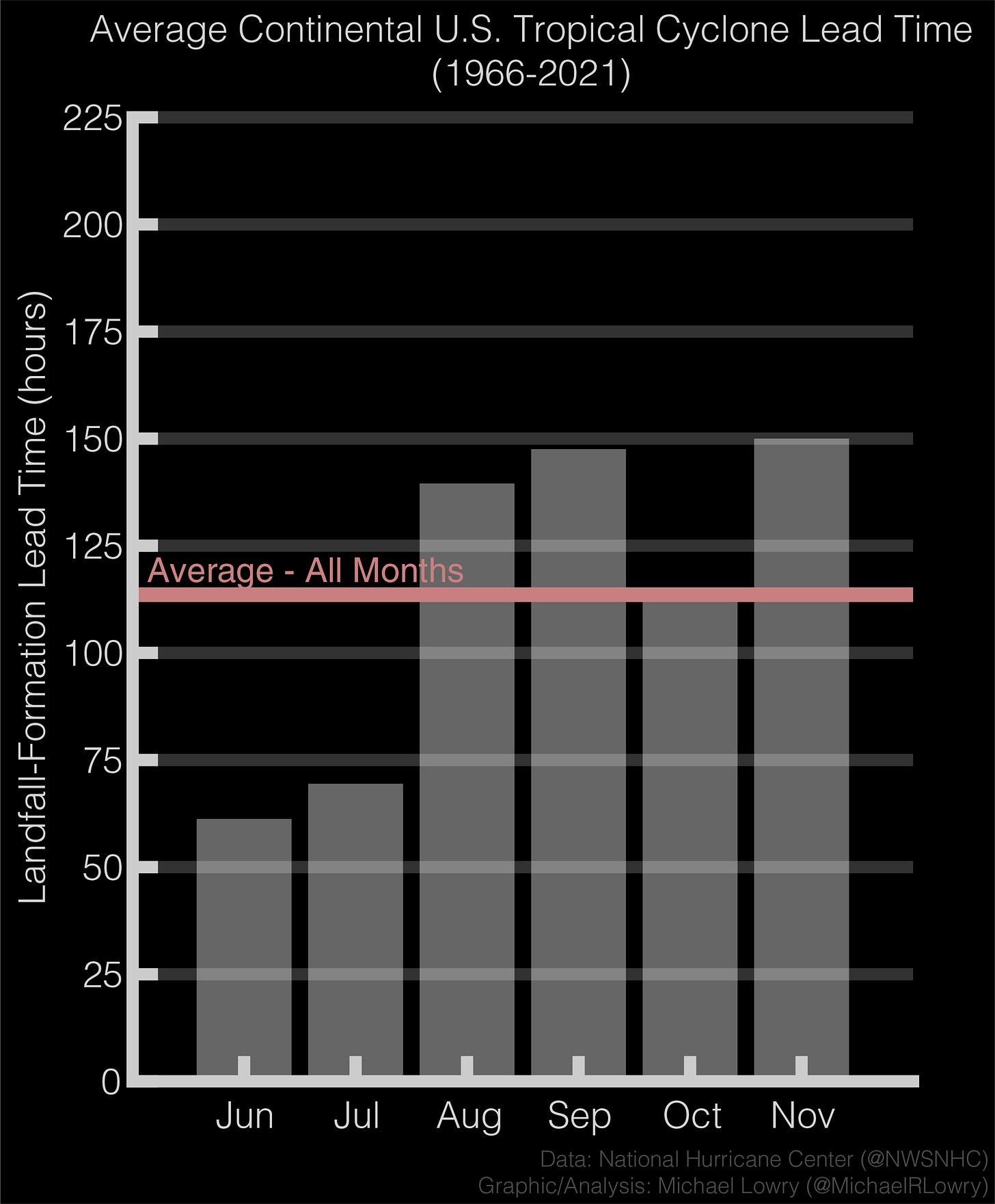

In fact in June, we have, on average, less than half as much notice for a tropical cyclone impact than in August or September. The time from formation to landfall in the continental U.S. averages only about 60 hours in June versus storms forming in September that average about 150 between birth and landfall – almost a full week’s notice.

That said, even hurricanes later in the season can both form and strengthen quickly. Hurricane Michael in 2018, for example, took a mere 83 hours between becoming a tropical depression on Sunday morning to making landfall as a Category 5 hurricane on Wednesday afternoon in the Florida panhandle. Michael was a primary catalyst for us designing an abbreviated hurricane response playbook during my time with FEMA. So much of what emergency managers do – from positioning food and water to activating evacuation contracts to staging search and rescue teams to evacuating at-risk populations – require days to complete. Not every storm will give us the luxury of a week leadup before landfall, so the onus is on us to prepare early for what even the best hurricane forecast may miss.